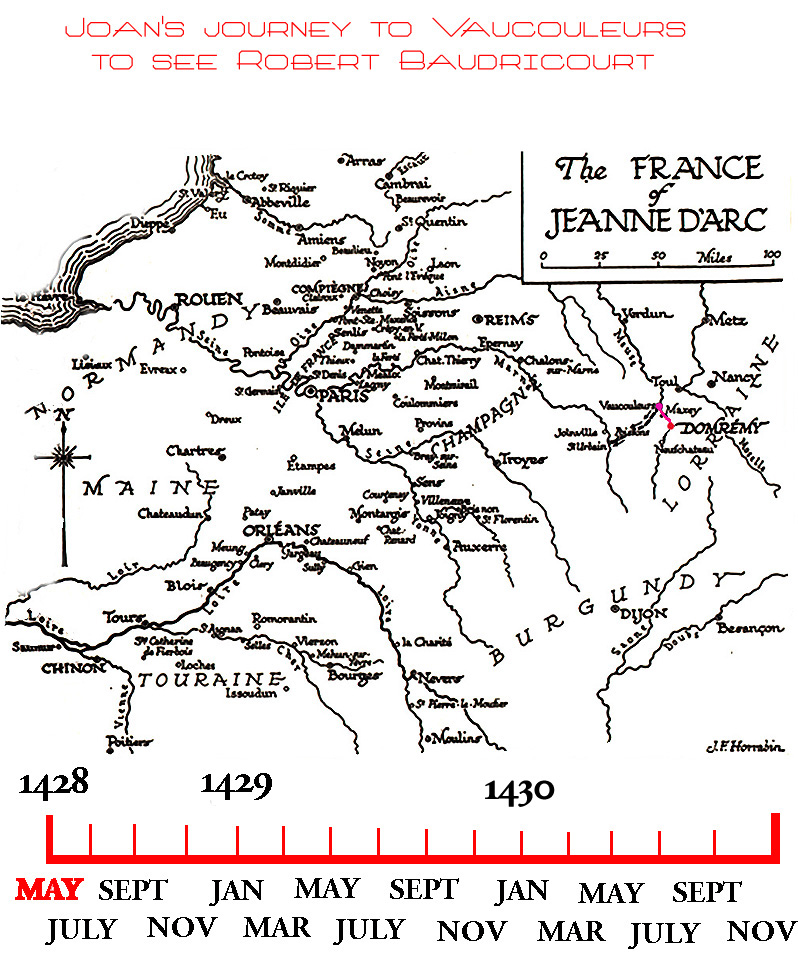

Joan’s journey to Vaucouleurs to see Robert Baudricourt

Domremy:

Joan was born in Domremy, a small village on the frontier of the duchy of Lorraine. The district was ruled directly by the royal administration and remained loyal to Charles VII despite its being within a predominantly Anglo- Burgundian area.

The towns of Vaucouleurs, Greux, Neufchateau, and Maxey lie near Domremy, as does the river Meuse. Though the inhabitants of Domremy occasionally experienced nearby skirmishs, for thier life was easier than it was most in France at the time. Domremy showed no signs of social breakdown, unlike most areas of France. However, the town was partially burned by a band of Anglo- Burgundians who drove off the village’s cattle in 1425. This is the same year Joan’s visions began.

View photos of Domremy here.

Vaucouleurs: In December, 1428, Joan left her village for the town of Vaucouleurs with a relative. Vaucouleurs administerd much of the near-by village of Domremy and had remained loyal to the dauphin. Durand Laxart, the relative Joan left with, was a cousin of Joan’s though she called him uncle since he was fifteen years older than her. It appears that she did not have too much difficulty persuading him to take her to see Robert de Baudricourt, though her parents did not approve of her going. Sire de Baudricourt had been captain of Vaucouleurs since 1420. He, along with a few of his men, were the first to give Joan support for her mission to see the dauphin. It was also in Vaucouleurs that Joan first put on men’s dress. (References: Lucie-Smith, Edward. Joan of Arc. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc., 1976.)

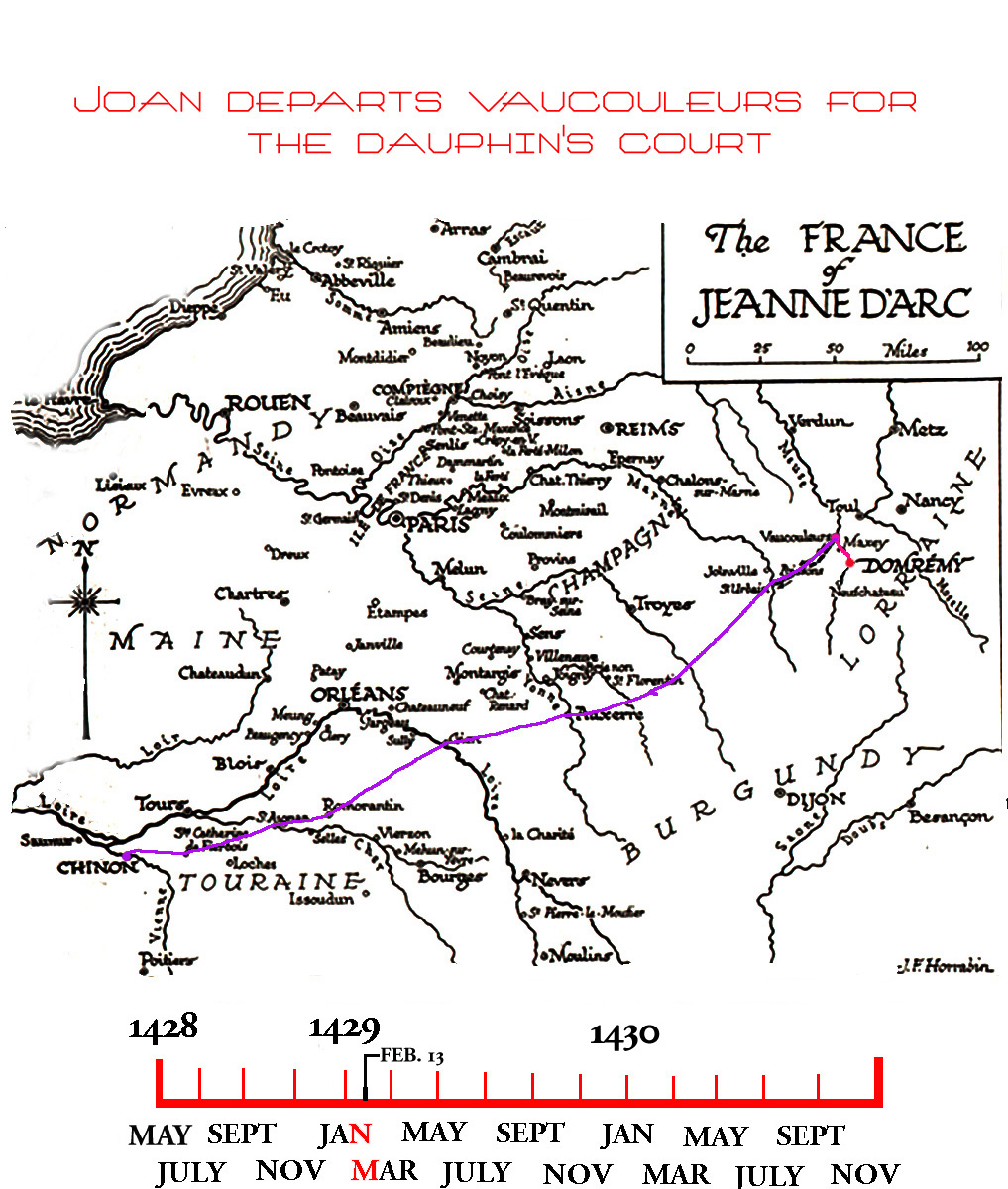

Joan departs Vaucouleurs for the Dauphin’s court

Ste. Catherine Fierbois: In Touraine, not far from Chinon, lies the Church of Saint Catherine de Fierbois. After Joan was validated by the Dauphin but before she went to Orleans, Joan sent an armorer to collect a sword that was buried behind the altar of this church. She later testified that her voices told her the sword would be there. Charles Martel (Charlemagne’s grandfather) left the sword in the chapel to commemorate his 732 victory in excising the Saracens. Joan loved the sword because of its relationship to Saint Catherine. Joan also stayed in the rectory near the chapel the night before she reached Chinon.

Chinon: Joan journeyed from Vaucouleurs to Chinon for eleven days with six companions: Squire Jean de Nouillonpont (also called Jean of Metz), Squire Betrand de Poulengy, Julien (Betrand’s servant), Jean of Honnecourt (Jean of Metz’s servant), the royal messenger Colet de Vienne, and his servant Richard Larcher. Chinon’s chateau is actually three castles in one and is strongly built. The castle is on a high ridge above the town which offers a good defensive position with steep drop offs on each side. This was a favorite residence of Charles VII in part perhaps because the Royal Lodging was a separate building from the main portion of the castle offering the Dauphin some degree of privacy and separation. Joan first met Charles in the Great Hall of the Royal Lodging. It took a great deal of debating among Charles VII and his advisors before they decided to allow Joan to see the him for some of them feared she might be mad. Once Joan was permitted to present herself before the court they tested her by saying another extravagantly dressed lord was the King. Joan was not fooled nor intimidated however and calmly delivered her message to the true Dauphin. The Maid was able to persuade him to listen to her but he sent her on to Poitiers to be examined by prelates, theologians, and masters of the university so that he could be assured that Joan was not a witch. (References: Lucie-Smith, Edward. Joan of Arc. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc., 1976. Pernoud, Regine. Course Reader Volume I., trans. Jeremy DuQuesnay Adams. Dallas: Impressions, 1997. )

Poitiers: After seeing the Dauphin at Chinon, Joan was taken to Poitiers. There, she was examined by a group of churchmen who were appointed by the King. They met at several locations within Poitiers including: the house of a woman called La Macee and the Hotel de la Rose. Years later, one of the towers in Poitiers is still called ‘Tour de la Pucelle’ in memory of Joan.

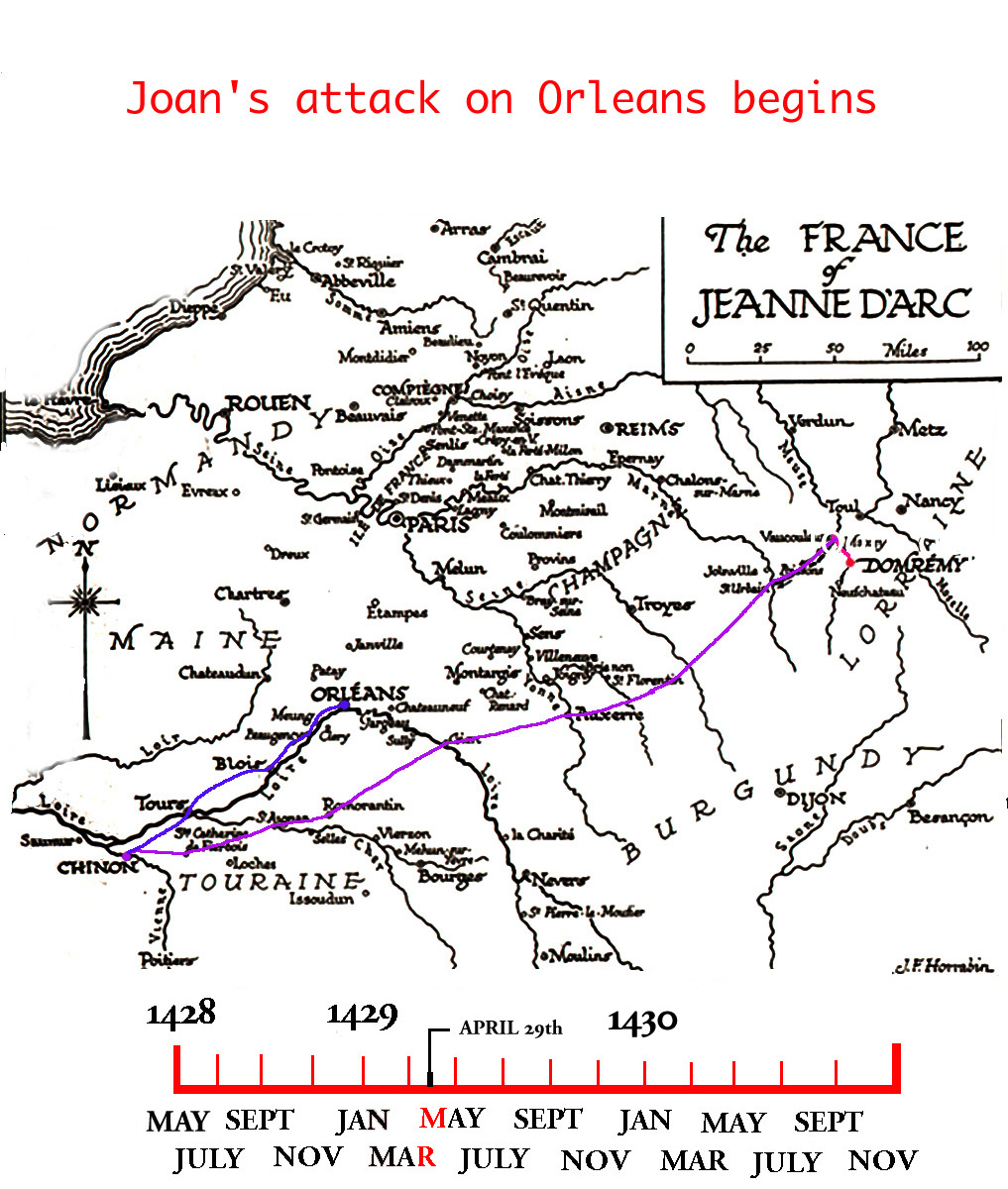

Joan’s attack on Orleans begins

Orleans: The ancient city of Orleans has existed since at least the 4th century and has been everything from a Carnute trading post to a rival with Paris for the Capetian’s center of royal government. After 1344, the dukes of Orleans were all close relatives of the French Kings. Philip, the younger son of Philip VI ruler until his death in 1375 when Louis, brother of Charles VI became both Duke of Orleans and the leader of the anti-Burgundian or Armagnac faction. Louis was assasinated and Charles d’Orleans was Duke during Joan’s time. Since he was captured at Agincourt and still held by the English at the time of the siege of Orleans, many felt that the English were breaking the chivalric code by attacking a city whose lord was imprisoned.

The English began the siege of Orleans on October 12, 1428 and the French made several unsuccessfeul attempts to relieve the city including the Battle of Herrings on February 12. Charles d’Orleans’ illegitimate half-brother John the comte de Dunois, commonly known as the Bastard of Orleans, took charge of leading the defense of Orleans. Joan entered the city on April 29, 1429 and within a few days she and the French army had captured several of the English held bastilles. On May 8, 1429, the siege of Orleans was lifted with the aid of Joan. (References: Medieval France: An Encyclopedia. Eds. William Kibler and Grover Zin. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1995. Pernoud, Regine. Course Reader Volume I., trans. Jeremy DuQuesnay Adams. Dallas: Impressions, 1997.)

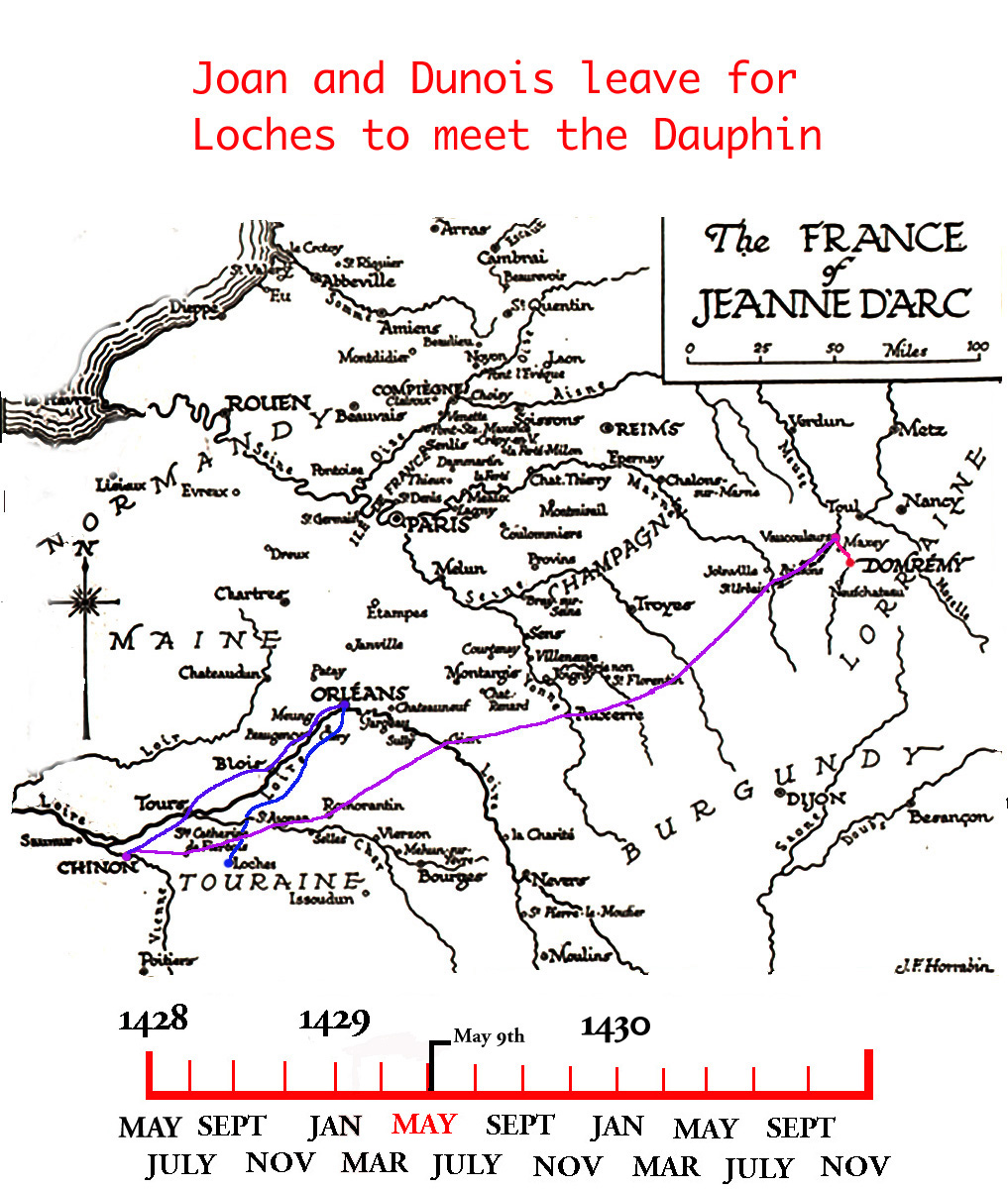

Joan and Dunois leave for Loches to meet the Dauphin

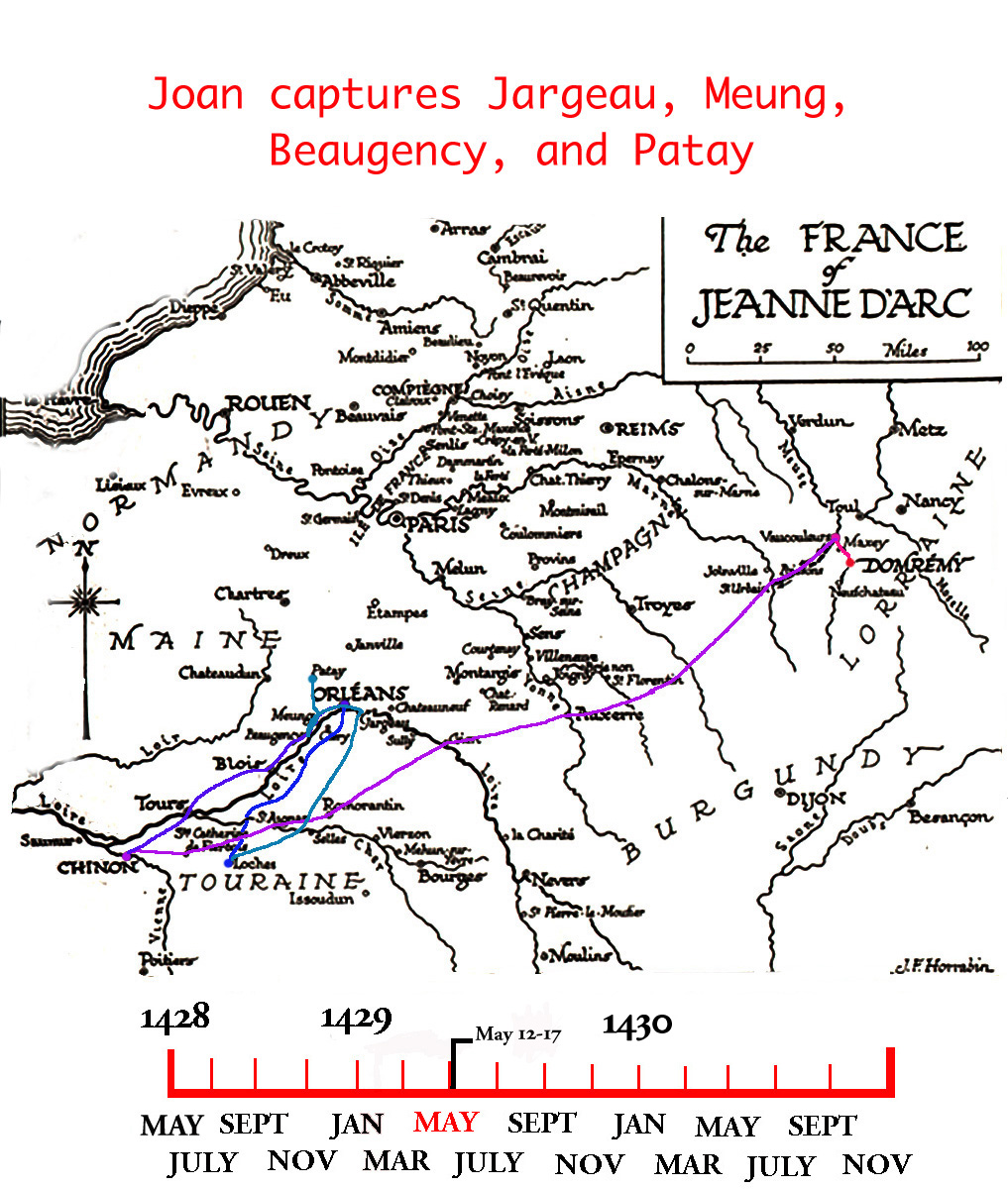

Joan captures Jargeau, Meung, Beaugency, and Patay

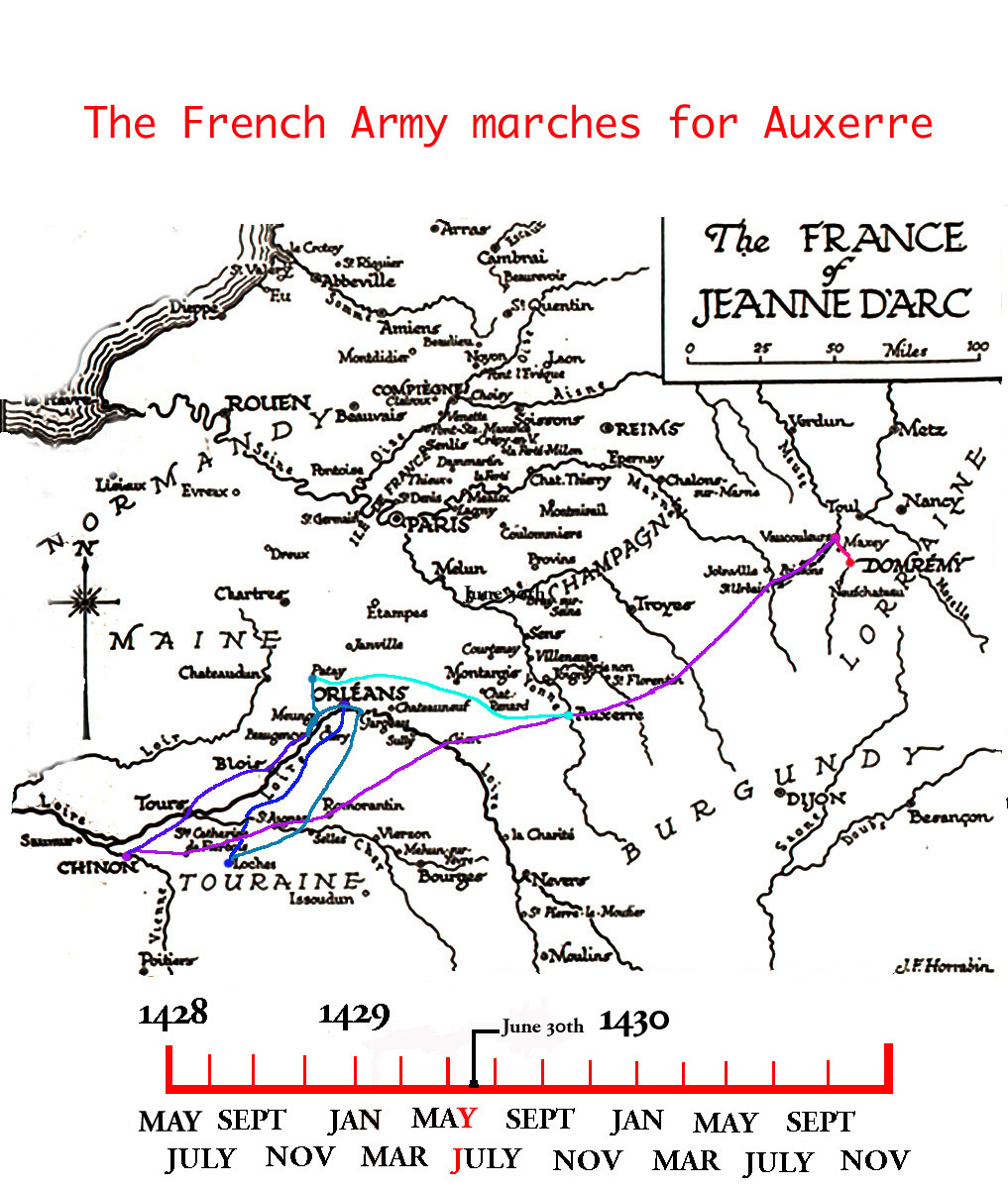

The French Army marches for Auxerre

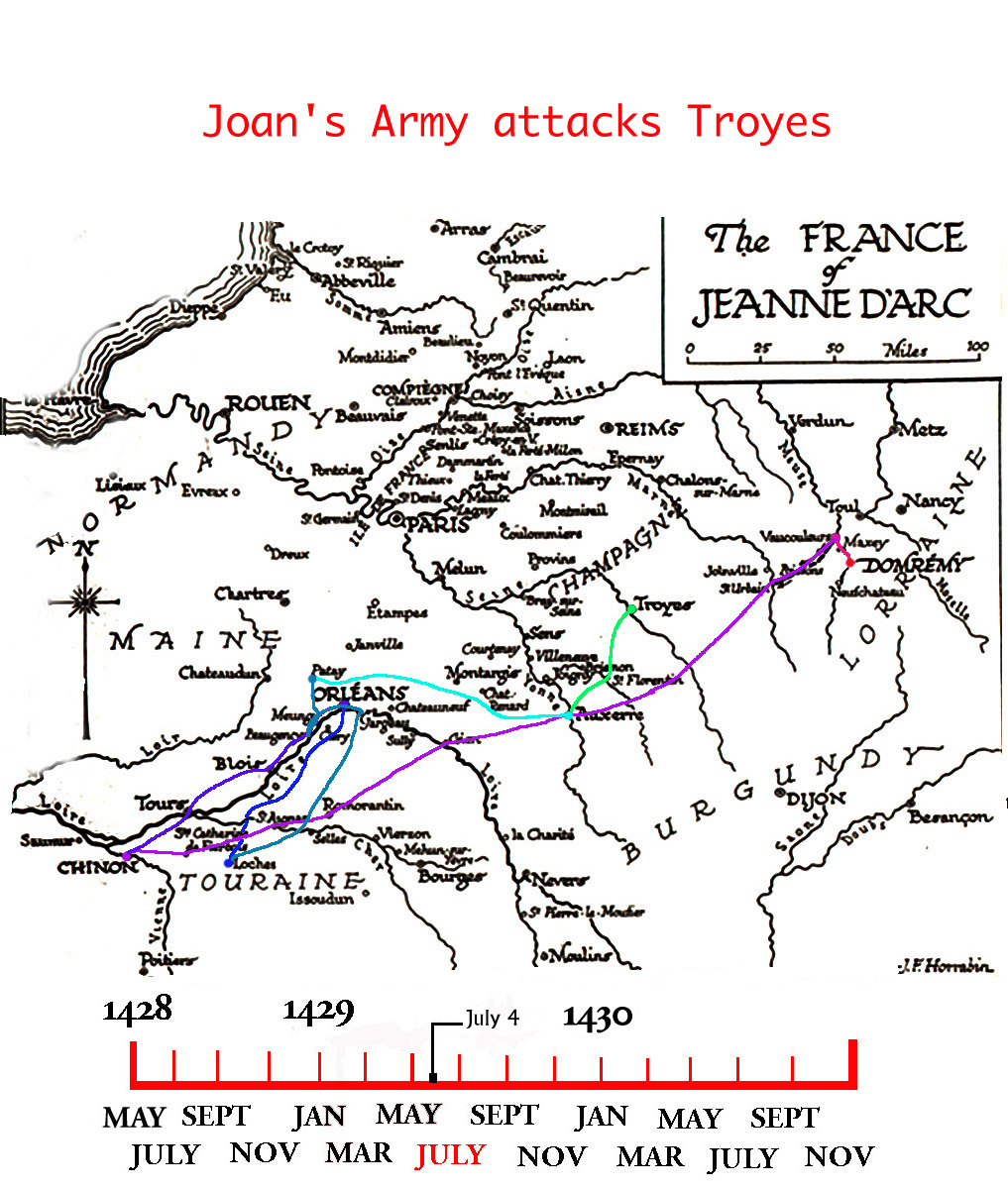

Joan’s Army attacks Troyes

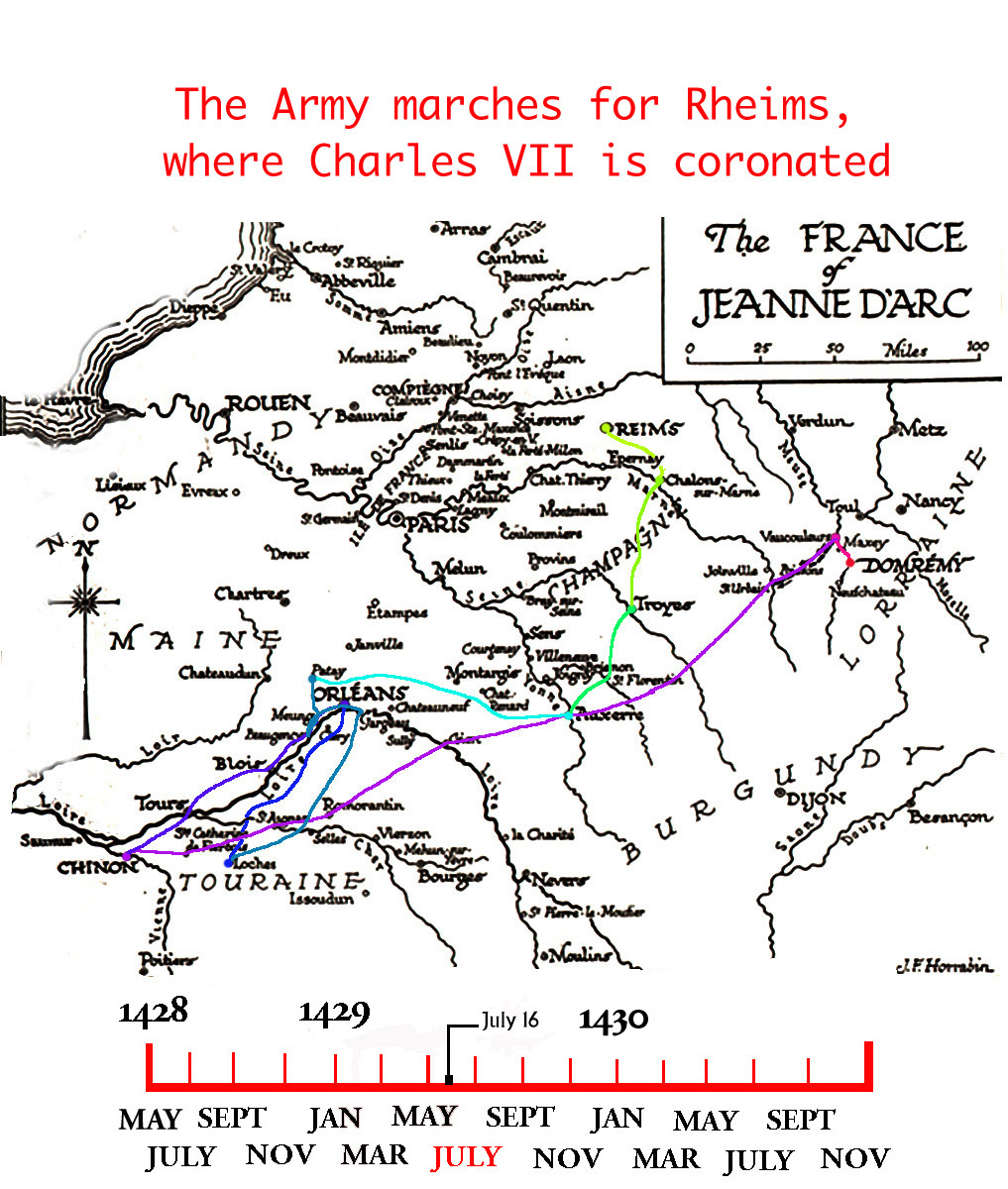

The Army marches for Rheims, where Charles VII is coronated

Rheims: After her great victory at Orleans, Joan was able to persuade the Dauphin to go to Rhiems to for his coronation. Rheims was the traditional site for holy coronations so it was important that he be crowned there even though Rheims was located dangerously close to the Anglo-Burgundian’s armies. In the eyes of Joan as well as many of the French people, Charles would not be the true King until he was annointed with the holy oil at Rheims. Many important French nobles, captains, and clergy were present including Joan herself who stood beside the King holding her standard.

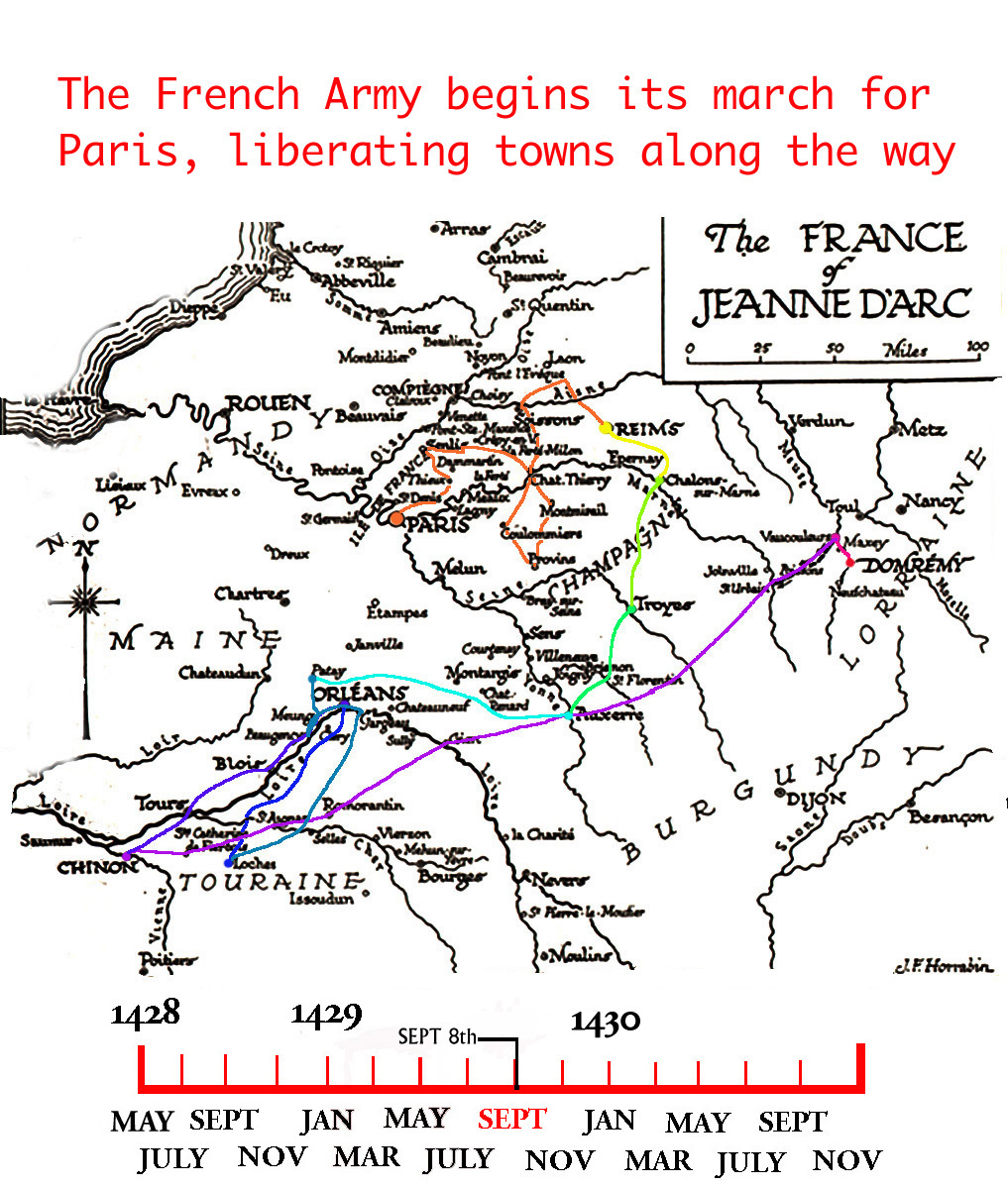

The French Army begins the long journey toward Paris, liberating towns on the way

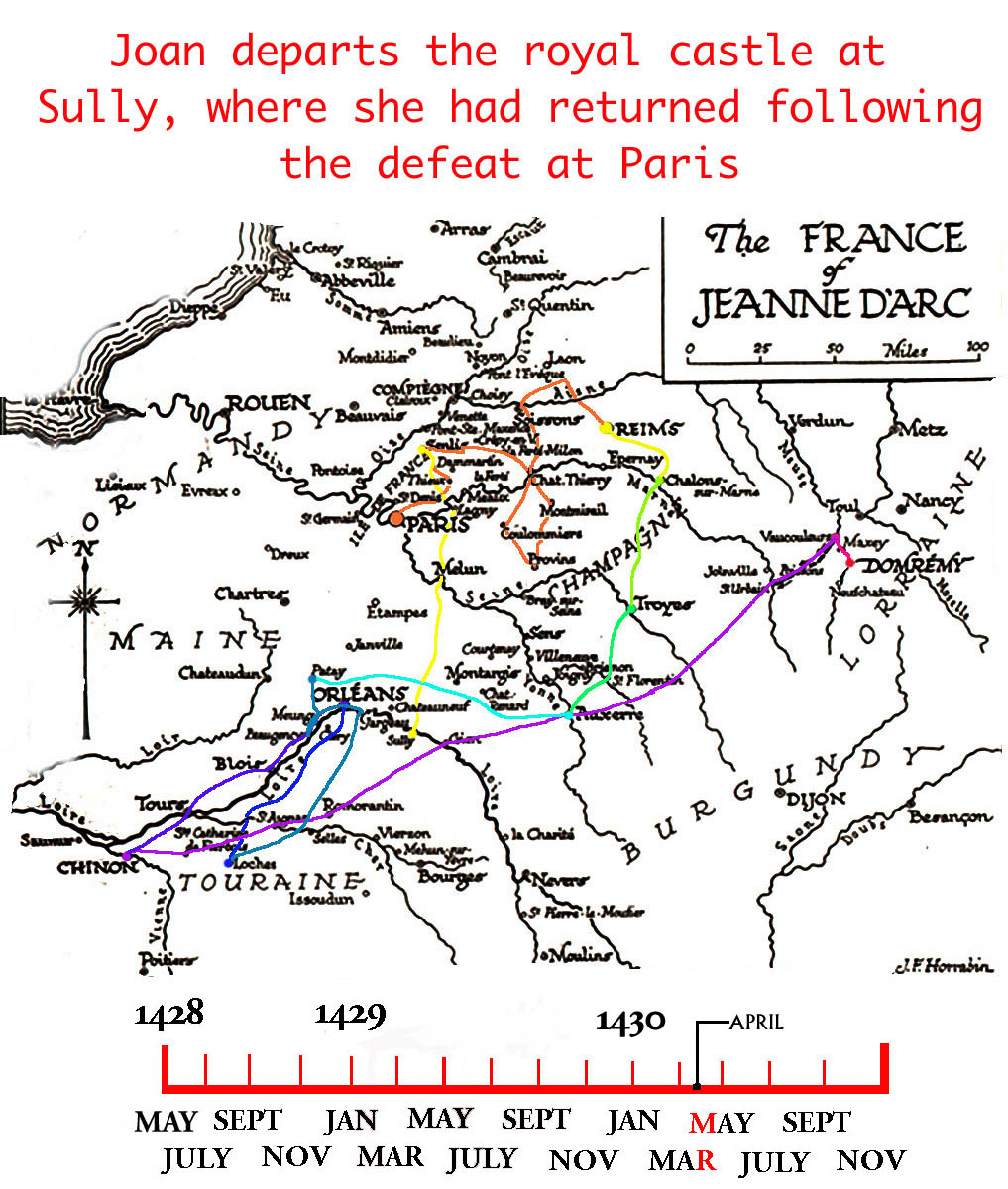

Joan departs the royal castle at Sully, where she had returned following the defeat at Paris

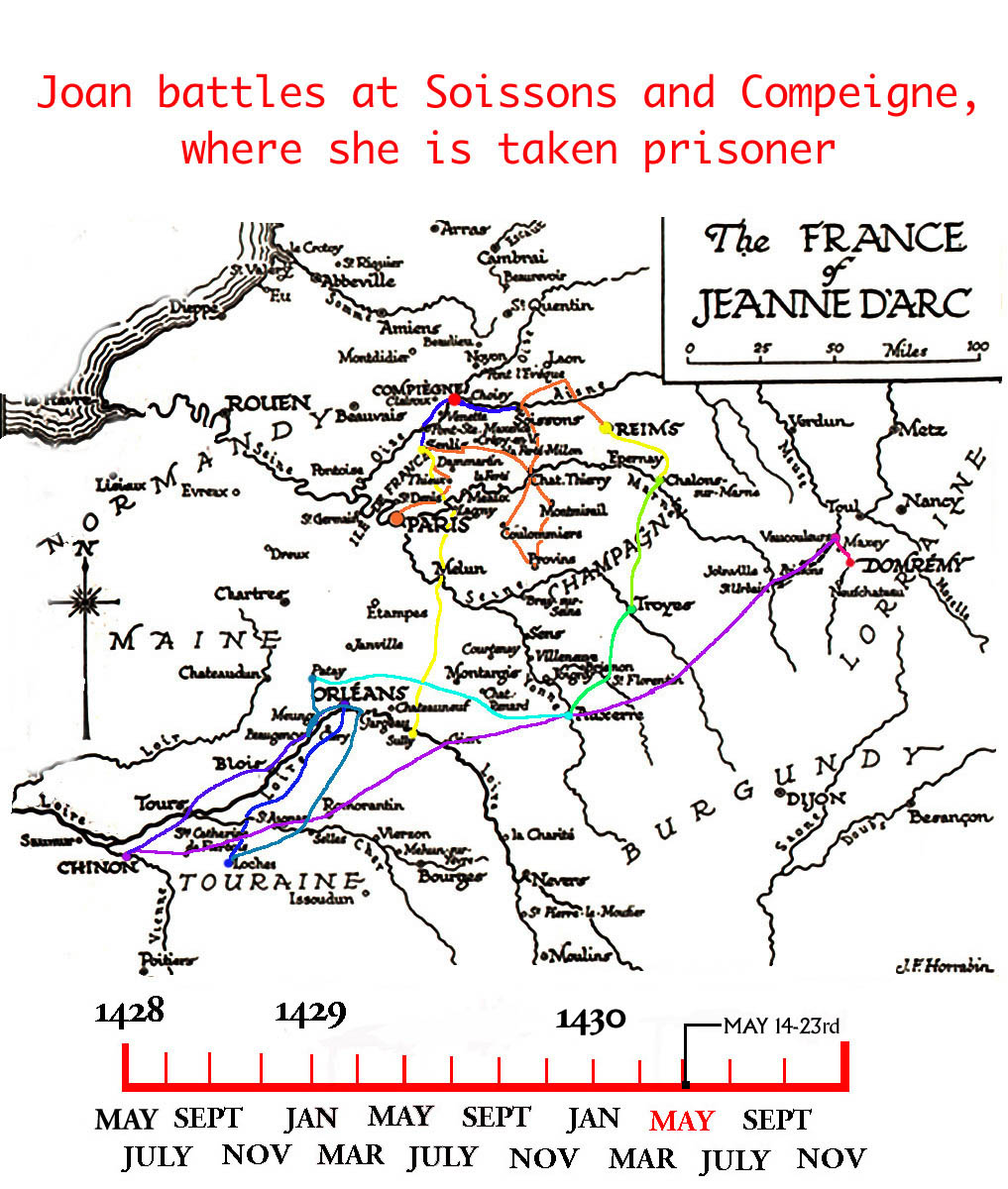

Joan battles at Soissons and Compiegne, where she is taken prisoner

Soissons: On May 18, 1430, Joan entered Soissons. She had planned to use the bridge there to take the enemy from behind. However the towns captain, Guichard Bournel, sold the town before she had a chance to. When Joan heard of this she was furious and replied that “if she could get ahold of said captain she would cut him into pieces.” Joan left Soissions to return to Compiegne on May 19. (References: Lucie-Smith, Edward. Joan of Arc. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc., 1976.)

Compiegne: Joan entered Compiegne on May 14, 1430, shortly after it became evident that the town would soon be besieged by the Burgundians. The town lies to the north of Paris at the joining of the Oise and Aisne rivers with Normandy just on the other side of the Oise. Joan left for Soissons but returned within a few days. She made a sortie with 500 men and was trapped outside the city when the French were forced to raise the drawbridge before everyone could make it back to safety. Joan was pulled from her horse and captured by the Burgundians on May 23, 1430, just outside the city’s walls. (References: Lucie-Smith, Edward. Joan of Arc. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc., 1976.)

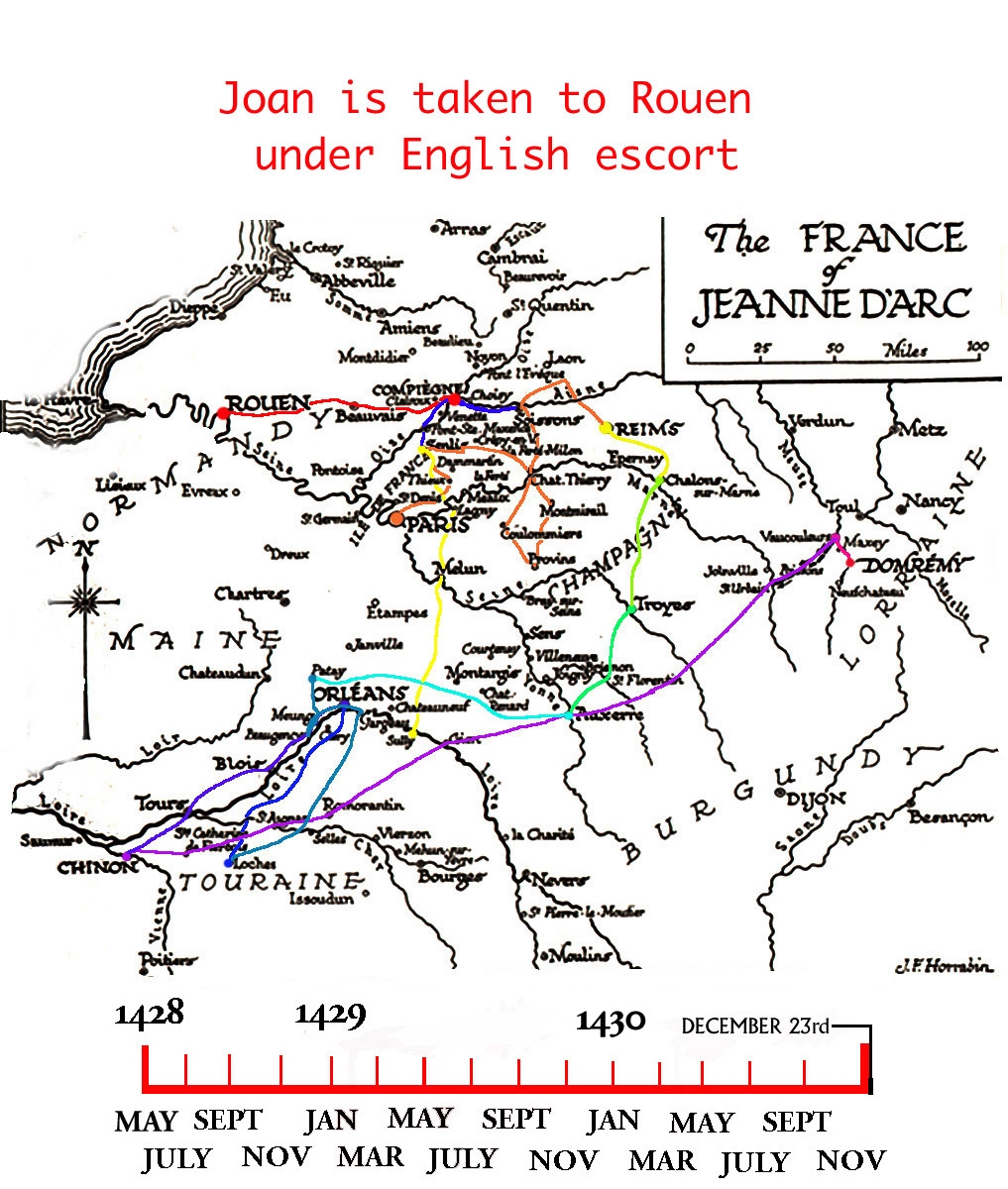

Joan is taken to Rouen under English escort

Rouen: Joan was brought to Rouen under English escort on December 23, 1430. Rouen sits along the Seine in the middle of the Province of Normandy and was important to England for its flourishing luxury trades. The castle in Rouen consists of seven towers surrounding a large lower court in the fortress of Bouvreuil. Joan was held in one of these towers, which was a secular prison. One of these towers is called the Joan of Arc Tower, however modern scholars feel she was not imprisoned in that particular tower. She was held in this tower throughout the public hearings, private interrogations, inquiry, and the trial itself until she was turned over to secular authority on May 30, 1421.

Joan’s cell was a dark room in the castle at Rouen. She was kept in leg irons which were chained to a large piece of wood. She was under the carefull guard of five English soldiers, three of whom slept within her cell. Though the imprisonment was clearly secular, the keys to her cell were held by three clergymen) Cardinal Henry Beaufort, Cauchon, and Inquisitor Jean Graverent) to maintain the legal illusion of it being an ecclesiastical custody. The tower Joan was held in allowed for others to easily hear what happened in her cell without being seen. (Lucie-Smith, Edward. Joan of Arc. New York: W.W. Norton Company Inc., 1976. Pernoud, Regine. Course Reader Volume I., trans. Jeremy DuQuesnay Adams. Dallas: Impressions, 1997.)